Typography

Origins

Letterforms

Properties of Letterforms

Typographic Measurements

Typesetting

Typography and Fonts

TrueType and PostScript Type 1

ASCII

Unicode

Text on the Web

Origins

Written language has evolved from pictorial representations of objects and

events into sophisticated systems of symbols representing spoken sounds. The

process had three stages:

Pictograms

Pictograms are drawings of fundamental objects and ideas such as man, woman,

spear, tree, and shelter. These were simple and literal representations, and

they were combined to form a visual storyboard. There was no connection between

the spoken word and the object pictured; a pictogram represented a mental

image of an object, not its name.

Cave painting from eastern Algeria.

Ideograms

Ideograms are simplified pictures selected by custom to become fixed pictorial

symbols of an object or concept. For example, a number of "tree" symbols are

unified to make a "forest," or the symbol for man, woman, and child are consolidated

into a single "family" symbol. As such the picture became more abstract. The

name of the object (or its action) is closely identified with the picture.

Male symbol (shield + spear).

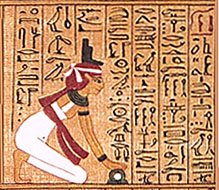

Phonograms

Phonograms are syllabic signs and symbols representing primary oral sounds.

As time passed, they they diminished in resemblance to their original forms,

but the letters in modern alphabets are the simplified renderings of their

pictorial beginnings.

|

|

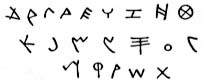

| Egyptian hieroglyphic. |

Phoenician alphabet. |

|

|

The modern Greek alphabet.

Derived of Phoenician and Semitic languages, ancient Greek added the

five vowel sounds (a,e,i,o,u) making it a truly phonetic language. By

600 BC it was written from left to right. The word "alphabet"

comes from a concatenation of the first two Greek letters, alpha - beta.

|

top of page

Letterforms

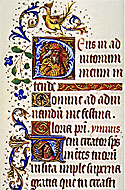

Although the basic letterforms of the modern Western alphabet have changed

little since the days of ancient Rome, the appearance of written and printed

letters evolved over time. These variations in style are due largely to changes

in the tools used for writing and printing.

- stone-carved letters of ancient Roman monuments

- hand-drawn illuminated manuscripts of gothic monks

- hand-cut wooden type used in early printing

- acid-etched metal type

- photo lithography

- typefaces designed for modern digital output

|

|

| Illuminated manuscript. |

Woodblock print, 1466. |

|

|

|

Avant Garde magazine cover, by Herb Lubalin.

|

|

|

top of page

Properties of Letterforms

I. Serif and Sans Serif

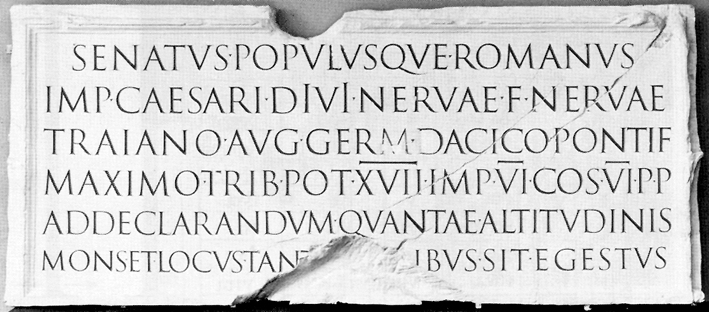

The type design that was used by the Romans is named Capitalis Quadrata. Capitalis

Quadrata was successively developed by the Romans from the original Greek alphabet,

and was introduced around 200 BC.

|

|

|

|

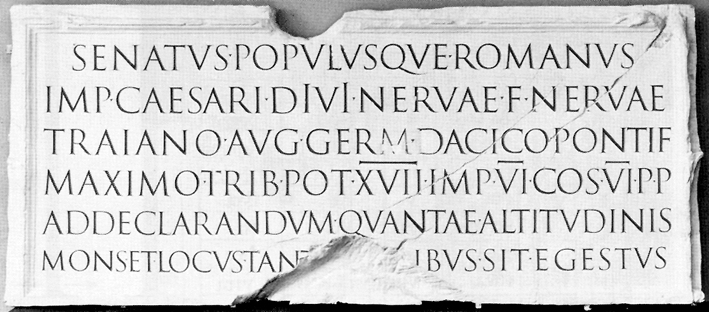

| Inscription from Trajan's column in Rome. |

Roman capital.

|

Serif letterforms relate aesthetically to the architecture of the buildings

or monuments they adorned. They are considered classical.

capital, in architecture

in architecture, the crowning member of a column, pilaster, or pier. It acts

as the bearing member beneath the lintel or arch supported by the shaft and

has a spreading contour appropriate to its function.

— The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001.

Sans Serif literally means "without serif". These letterforms emerged

in the latter half of the nineteenth century, and also reflect the architectural

style of their time.

|

|

| Skyline. |

Capital "I" in Arial Black typeface.

|

II. Case

The Roman alphabet only had capitals. The lower case letters, or Caroline miniscules,

are the result of Charlemagne (leader of the Holy Roman Empire, 800 - 814 AD)

and his efforts to create a consistent, more economical writing style. These

were the prototype for our modern small letters.

The names for these letters originated from where they were housed in the typeshop.

Capitals were stored in the upper section of a typecase, while small letters

were kept in the lower section. When setting type, a printer would take the

metal type from either the upper or the lower case.

III. Italic

The drawing of letterforms with a consistent, pleasing slant to the right is

called "italic", referencing the style of Italian calligraphers.

Italics are often used to add emphasis to a line of text.

IV. Stroke weight

Calligraphers used a reed pen held at a constant "cant", or angle,

to render type. This produced thick and thin strokes for each letterform. Serif

letterforms typically have varying stroke widths. Sans Serif letterforms, however,

usually have consistent stroke weight. Letterforms with heavy strokes are called

"bold".

BOLD CAPITAL LETTERS GET ATTENTION.

Typographic Measurements

Point size

In the western world there are two traditional systems in use for specification

of typographical measures. Both systems use the notation of a graphical point

as their smallest unit of absolute length, but those two points are not equal

in size.

On the European continent the Didot system is the one most widely in use. The

basic point unit in this system is defined as 0.376 millimeters (1/68 inch).

In the United Kingdom and in America another variant of a point based measurement

system is prevalent, the Anglo Saxon system. Today the basic point of the Anglo

Saxon system is defined as 1/72 of an inch.

In the US, a pica is a printer's measure, approximately refering to the height

of a line of text, and there are 12 points to a pica. There are 6 picas to an

inch. A point is approximately equivalent to one pixel on a 72 DPI monitor.

The em and en

The origin of a square as a relative unit of length for layout of characters

dates back to the Roman Empire. The most characteristic part of Capitalis Quadrata

is that all of its letters are designed within a specific relationship to a

square drawn from the height of the type.

Not all letters in the Roman alphabet filled the full width of the square,

but the letter "M" did. Thus the font height is defined by a universal

unit of length by the name of one "em". That 1:1 relationship between the width

of the letter "M" and the width of an "em" has been modified

over time. The invention of lower case letters introduced descenders, and after

1000 AD diacritical marks make their appearance, adding even more to the height

of a type. The size of the square, and hence the em, increased to cover both

descenders and diacritical marks.

Ü Ñ Á

Traditionally the em has been used to create white space areas in typeset text.

It's the standard measurement for text indents, together with another block

of white space that is exactly half as wide, the half square. The width of the

half square has also been given a name of its own as one "en".

dash -

em dash —

The x height

The x height is another relative length unit that is derived from the height

of a font's lower case letters that do not have descenders (i.e. the height

of the letter "x").

Line spacing, or leading

The line height is defined as the distance between the baselines of two consecutive

lines of text. Introduction of extra white space between lines of text was traditionally

done through a process called leading. The typesetter inserted thin strips of

brass with a known thickness between lines of type blocks in the printing frame

to increase the distance between the baselines of his types.

Kerning

Kerning is the space between letters, which can be increased (> 100%) or

reduced (< 100%). Certain character pairs, like the capital "T"

and the lower case "o" will appear to have too much white space between

them when set normally. Kerning tables embedded in modern digital fonts make

allowances for these pairs automatically.

top of page

Typesetting

|

|

|

|

Phaistos Disc, a terra-cotta disc found in Crete

with 31 groups of characters, 1700 BC.

|

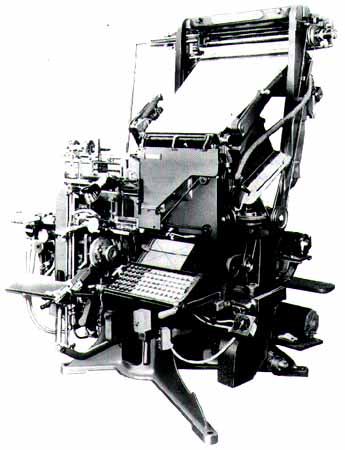

Linotype machine.

|

From the middle of the fifteenth century to the middle of the twentieth, most

printing used a technique where each letter is carved in wood and then cast

in lead. These letters were placed, or set, in a printing press, where they

were inked and printed onto paper.

Typesetting became automated in the late 1800s as a result of the invention

of the Linotype and Monotype machines. Operators of these machines used a keyboard

to set type, which was then cast in hot metal for use in a printing press.

Phototypesetting, introduced in the 1950s, did away with metal type completely.

Photoype systems produce film negatives or digitized images, which are then

printed using offset lithography.

Modern digital typesetting systems encode typographic characters, defining

each letter by the position of points on a grid. The quality of the output depends

on the number of dots per inch (DPI) the output device is capable of producing.

The growing accessibility and pervasiveness of digital devices such as computers,

PDAs, cell phones, and digital projectors have given rise to many "on-screen

only" applications for type. Because these letterforms are created through the

combination of pixels, the quality and legibility of the type these devices

can display is limited by the screen resolution (measured in pixels) each is

capable of.

The illusion of smoothness of on-screen type is created through anti-aliasing.

However, this technique causes elements of letterforms, such as the thick and

thin strokes of serif typefaces, to lose legibility, especially at lower screen

resolutions. This has led to the design of typefaces, so-called "pixel fonts",

specifically for digital display that are legible at smaller sizes because they

do not require smoothing.

top of page

Typography and Fonts

The word "font" refers to a foundry where metal type was cast. It

describes all the variations of a type design. Font is synonymous with "typeface".

Below are some general categories of fonts:

|

|

|

Monospace fonts, such as Courier, are derived from typewriter

fonts, where letter widths had to be uniform. They are used sometimes

to distinguish computer code from body text.

|

Symbol fonts are used in cartography, architectural

renderings, and musical notation. |

|

|

|

Serif fonts, like Times Roman, are more traditional designs and

are considered the most legible. They are often used to set body copy

in print. On computer screens, however, at small point sizes, their detail

is lost due to antialiasing.

|

Screen fonts are designed primarily for use on mobile

computing devices like PDA's, and are not meant for printing. |

|

|

|

Sans Serif fonts, like Helvetica, are modern looking. Typically

the strokes have consistent weight.

|

Display fonts, like Glaser Stencil, are designed for

use in headlines, not for body copy. Many do not have a lower case. |

|

|

| Calligraphic fonts have strokes that vary in thickness,

and the letterforms are slanted, like italic versions of other fonts. |

Language fonts often require unique keyboard mappings. |

Each typeface can have many variations including bold, italic, and condensed

versions. A table of all the characters in a font (upper and lower case, numerals,

punctuation, and special characters) is called a type specimen.

Typographic design has always been the most skilled of the graphic arts, from

the days when typographers had to etch metal plates with their designs, to today

when they have to program the outlines of a digital font. Thus many fonts are

named after their designers, such as Caslon, Baskerville, Bodoni, Goudy, or

Lubalin.

top of page

TrueType and PostScript Type 1

TrueType (TT) and PostScript Type 1 (PS1) are both multi-platform outline font

standards for which the technical specifications are openly available. "Multi-platform"

means that both font types are usable on multiple sorts of computer systems.

"Outline font" means that they describe letter shapes ("glyphs") by means of

points, which in turn define lines and curves.

This representation is resolution independent, meaning that outlines, by their

very nature, can be scaled to pretty much any arbitrary size. But an outline

font must be represented by the dots of the output device. The process of converting

the outline to a pattern of dots on the grid of the device is called "rasterization."

When there aren't enough dots making up the glyph (such as at small sizes or

low resolutions), there can be inconsistencies in the representation of certain

letter features, at a single size, due to different rounding based on how the

outline happens to sit on the grid. A common form of this is that the widths

of the letter stems can vary when they shouldn't. Worse, key features of the

glyphs can disappear at small sizes.

However, PostScript Type 1 and TrueType fonts both have a means of dealing

with these inconsistencies, called "hinting." This consists of additional information

encoded in the font to help prevent these problems by using interpolated values.

top of page

Character Mappings

ASCII

The American Standard Code for Information Interchange is a standard seven-bit

code that was proposed by ANSI (American National Standards Institutue) in 1963,

and finalized in 1968. ASCII was established to achieve compatibility between

various types of data processing equipment.

ASCII is the common code for microcomputer equipment. The standard ASCII character

set consists of 128 decimal numbers ranging from zero through 127 assigned to

letters, numbers, punctuation marks, and the most common special characters.

The Extended ASCII Character Set also consists of 128 decimal numbers and ranges

from 128 through 255 representing additional special, mathematical, graphic,

and foreign characters.

top of page

Unicode

Fundamentally, computers just deal with numbers. They store letters and other

characters by assigning a number for each one. Before Unicode was invented,

there were hundreds of different encoding systems for assigning these numbers.

No single encoding could contain enough characters: for example, the European

Union alone requires several different encodings to cover all its languages.

Even for a single language like English no single encoding was adequate for

all the letters, punctuation, and technical symbols in common use.

These encoding systems also conflict with one another. That is, two encodings

can use the same number for two different characters, or use different numbers

for the same character. Any given computer (especially servers) needs to support

many different encodings; yet whenever data is passed between different encodings

or platforms, that data always runs the risk of corruption.

Unicode provides a unique number for every character, no matter what the platform,

no matter what the program, no matter what the language. Unicode is required

by modern standards such as XML, Java, and JavaScript.

Unicode enables a single software product or a single website to be targeted

across multiple platforms, languages and countries without re-engineering.

top of page

Text on the Web

The Internet is not "type-friendly":

- Fonts specified by the author of a web page may not be resident on the client's

computer, or the author's choice can be overridden by the user.

- There is no direct correlation between the HTML specification for type size

and point size. Different browsers show the same size type as larger or smaller.

- Special character support is limited.

- There is no support for kerning.

- Certain fonts may require alternate keyboard mappings.

- Font color varies cross-platform.

- Unlike print, computer displays are low resolution.

HTML has very limited text formatting options, such as:

HEADING 1

|

strikethrough

|

sample

|

HEADING 6

|

teletype

|

keyboard

|

|

SIZE 7

|

strong

|

citation

|

|

SIZE -7

|

code

|

definition

|

To work around these limitations web designers have a couple of options:

- Make a picture of the type with the desired design options and embed it

in the page (usually a .gif).

- Embed the font as an outline in an application (like Shockwave) that is

handled by a plug-in, not the browser.

CSS

A style sheet is a set of parameters for displaying text on a web page, which

is looked up by the requested document. The text on the page is formatted according

to the specs of the style sheet referenced by the page. The use of Cascading

Style Sheets (CSS) for formatting text on web pages brings many benefits to

authors:

- Authors can make a change in one location that reformats the entire web

site.

- Formatting options are extended through the use of style sheets.

- There is a consistent style applied throughout the site.

top of page

References

The Evolution of Type (http://www.mediumbold.com/)

Typographical Measurement Systems (http://css.nu/articles/)

Thomas Pinney, "True Type and PostScript Type 1: What's the difference?"

(http://www.truetype.demon.co.uk/articles/ttvst1.htm)

www.unicode.org