Animation is not the art of drawings that move, but the art of movements that are drawn.

— Norman McLarenanimation

SYLLABICATION: an·i·ma·tion

NOUN: 1. The act, process, or result of imparting life, interest, spirit, motion, or activity. 2. The quality or condition of being alive, active, spirited, or vigorous. 3a. The art or process of preparing animated cartoons. b. An animated cartoon.— The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000.

Animation is more than merely rendering objects in motion. It is the art of bringing them to life.

Projection

Shadow Puppets:

Shadow plays originated in Java and India thousands of years ago. These thin

leather puppets are intricately perforated and painted, and depict figures in

folk lore. They are manipulated by rods in front of a translucent screen, lit

from behind so that the puppet is seen in silhouette by the audience on the

other side.

The Magic Lantern:

Invented in 1650, the magic lantern was the predecessor of the modern slide

projector. Lantern shows reached peak popularity in the Victorian era with the

invention of limelight in 1826. Magic Lanterns soon adapted the devices which

were able to control the volume of the gasses so as to raise and lower the light

levels on two or more lanterns and dissolve from one view to another. Oxygen

and hydrogen were burned on a limestone surface to produce limelight, which

was projected through colored scenes hand-painted on glass slides, resulting

in brilliant images that could be shown to up to hundreds of people at a time.

The term "limelight" has nothing to do with the color of the light

but rather the source, which is a form of limestone called calcium carbonate,

which is very bright when ignited. Lanternists would travel from town to town

with slides of current events, such as scenes from the Civil War. For many rural

communities this was a primary source of news.

|

Victorian Christmas Lantern show. |

A slide

from the serialization of Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin",

America's first best-selling novel. A slide

from the serialization of Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin",

America's first best-selling novel. |

|

Early Animation Devices

|

|

|

|

Thaumatrope On one side of a round board was drawn a bird; on the other was a cage. When the board was held at the sides by two strings and spun, both images merged and the bird appeared to be in the cage. |

Fantascope Basically a disc fixed at its center so that it can spin freely. Around the edges are regularly spaced slits, and in conjunction with each slit is an image drawn in sequential stages of movement. The person using the device would hold it between them and a mirror, with the images facing the mirror. When the disc was spun, the images were viewed, reflected by the mirror, through the passing slits. |

Zoetrope The image was drawn on a removable strip of paper, so the animations were changeable. The slits were equally spaced around the drum, and the images were spaced along with them. The viewer spun the drum and watched the animation through the slits. |

The Kineograph and the Mutoscope

The Kineograph was invented officially in 1868. It is also known as a flipbook,

and consists of drawings or photographs in sequential stages of movement bound

as a book. To view, the book was flipped through rapidly with the thumb. Thomas

Edison took the idea and in 1895 developed the Mutoscope, which was a sort of

mechanized version of the flipbook. These were popular amusements well into

the first half of the 20th century.

The Zoopraxiscope

In 1877, the governor of California had been involved in a bet that, as

a horse ran, all four of its legs left the ground. To prove his theory correct,

he hired Edward Muybridge, an itinerant photographer. Muybridge set up a series

of cameras, 12 of them originally, and connected them to wires. The wires were

broken in turn by a horse as it ran by, and the resulting images recorded true

stages of motion for the first time. The governor won his bet, and Muybridge

continued to photograph series of movements of all sorts of animals, as well

as people. Many of his studies were turned into zoetrope strips. He developed

the Zoopraxiscope, based on the projecting Fantoscope, to project his series.

It produced the first projected images of true motion.

Walking study by Muybridge.

Motion Pictures

George Eastman invented celluloid film in 1884. Thomas Edison and his staff

then developed the Kinetograph, a large, bulky camera, and the Kinetoscope,

a "peep hole" type machine for viewing the filmstrips. These were successful

entertainment, but could only be viewed by one person at a time. (An assistant

of Edison, William Dickson, developed in 1889 the Kinetophonograph, which produced

the earliest projected image with sound. Edison chose not to pursue the invention,

supposedly due to poor quality, and it would be almost 40 years before a commercially

viable sound motion picture system would be developed.) In 1895 the Lumiere

brothers invented the first practical portable cinema camera.

Animated drawings were introduced to film a full decade after George Melies had demonstrated in 1896 that objects could be set in motion through single-frame exposures. J. Stuart Blackton's 1906 animated chalk experiment "Humorous Phases of Funny Faces" was followed by the imaginative works of Winsor McCay, who made between four thousand and ten thousand separate line drawings for each of his three one-reel films released between 1911 and 1914. Only in the half-dozen years after 1914, with the technical simplifications involving tracing, printing, and celluloid sheets, did animated cartoons become a thriving commercial enterprise.

Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906).

The Dinosaur and the Missing Link: A Prehistoric Tragedy (1917).

Fifteen years before creating King Kong, former cartoonist Willis O'Brien animated

these clay-modeled dinosaurs and giant ape. He produced eight such one-reelers

for the Edison Company in 1917.

Gertie on Tour (1921).

One of the final films of master cartoonist Winsor McCay, it was animated in

collaboration with his son and a longtime assistant, John Fitzsimmons.

Brief History of Cartoon Studios

Winsor McCay animated his films almost single-handed. He took the time to make

his films unique artistic visions, sometimes spending more than a year to make

a single five-minute cartoon. Once public demand for animated films was established,

this process took too long, and animated cartoons entered the studio era. The

art of animation became a streamlined, assembly-line process. Because of studio

production characters like Felix the Cat could be serialized, unlike Gertie

the Dinosaur.

The most influential of these early studios was the the John Bray Studio.The

studio's most important contribution to the medium was the introduction of cels.

The process of inking the animator's drawings onto clear pieces of celluloid

and then photographing them in succession on a single painted background was

invented by Bray employee Earl Hurd in late 1914.

But the best known studio in the history of animation is the Walt Disney Studio,

which exploded onto the scene in 1928 with Mickey Mouse in "Steamboat Willie".

Disney steered cartoons away from the "rubber hose" style of the silent era

and encouraged his artists to develop a realistic, naturalist style of animation

in the early 1930s. He was the moving force behind such groundbreaking films

as "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" (1937), the first full-length animated

feature, and "Pinocchio" (1940).

"Looney Tunes" began in 1930, and the Warner Bros. studio used the assembly-line

system to render their characters. This is exemplified in the development of

Bugs Bunny. It took over 10 years and 30 films for Bugs to become the comic

hero we know today. The legendary animators of the Warner Bros. shop are Chuck

Jones, Fritz Freleng, and Tex Avery.

Production of TV animation didn't really hit its stride until about 1960, when

most of the cinematic cartoon studios had shut their doors. Bill Hanna and Joe

Barbara, former MGM directors and creators of Tom and Jerry, dominated the market

from its inception and continued to do so through the 1970s. Hanna-Barbara cartoons

were mass-production, with flatly rendered characters and scenes and formulaic

stories, typified by "The Flintstones".

Straight Ahead Action

Is when the animator starts at the first drawing in a scene and then draws all

of the subsequent frames until he reaches the end of the scene. This creates

very spontaneous animation and is used for wild, scrambling action.

Pose-to-Pose Action

Is when the animator carefully plans out the animation, draws a sequence of

poses, i.e., the initial, some in-between, and the final poses and then draws

all the in-between frames (or another artist or the computer draws the inbetween

frames). This is used when the scene requires more thought and the poses and

timing are important.

Keyframing

Keyframe systems were developed by classical animators such as Walt Disney.

An expert animator would design (choreograph) an animation by drawing certain

intermediate frames, called Keyframes. Then other animators would draw the in-between

frames. The sequence of steps to produce a full animation would be as follows:

1. Develop a script or story for the animation

2. Lay out a storyboard, that is a sequence of informal drawings that shows the form, structure, and story of the animation.

3. Record a soundtrack

4. Produce a detailed layout of the action.

5. Correlate the layout with the soundtrack.

6. Create the "keyframes" of the animation. The keyframes are those where the entities to be animated are in positions such that intermediate positions can be easily inferred.

7. Fill in the intermediate frames (called "inbetweening" or "tweening").

8. Make a trial "film" called a "pencil test"

9. Transfer the pencil test frames to sheets of acetate film, called "cels". These may have multiple planes, e.g., a static background with an animated foreground.

10. The cels are then assembled into a sequence and filmed.

With computers, the animator would specify the keyframes and the computer would

draw the in-between frames ( "tweening"). The simplest type of interpolation

is linear, i.e., the computer interpolates points along a straight line. A better

method is to use cubic splines for interpolation. Here, the animator can interactively

construct the spline and then view the animation.

top of page

Animation is not merely recording the movement of objects. For animation to be convincing, it must exaggerate motion. Several principles are described below:

Posing

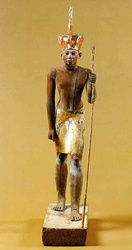

In the modeling and posing of human figures we can use examples from sculpture.

Early sculptures of human figures, while anatomically correct, appeared stiff

and unnatural. The classical Greeks progressed to where they were able to model

the human form in a nonsymmetrical, relaxed stance that appeared much more realistic.

This is described by the Italian word Contrapposto (counterpoise). This was

lost during the dark ages and was rediscovered during the Italian Renaissance.

If the keyframe poses are more credible then the interpolated (tweened) frames

will be more believable as well.

|

|

|

Egyptian sculpture

|

Michelangelo's David

|

Squash and Stretch

When real objects move only totally rigid ones, like a chair, remain rigid in

motion. Living creatures always deform in shape in some manner. For example,

if you bend your arm, your bicep muscles contract and bulge out. They then lengthen

and disappear when your arm straightens out. An important rule is that the volume

of the object should remain constant at rest, squashed, or stretched. If this

rule is not obeyed, then the object appears to shrink when squashed and to grow

when stretched. A classic example is a bouncing ball, that squashes when it

hits the ground and stretches just before and after. The stretching, while not

realistic, makes the ball appear to be moving faster right before and after

it hits the ground.

Ease In / Ease Out

This refers to the spacing of the inbetween frames at maximum positions. Rather

than having a uniform velocity for an object, it is more appealing, and sometimes

more realistic, to have the velocity vary at the extremes.

Click here to see an example of Squash and Stretch, Ease In / Ease Out

Timing and Motion

The speed of an action, i.e., timing, gives meaning to movement, both physical

and emotional meaning. The animator must spend the appropriate amount of time

on the anticipation of an action, on the action, and on the reaction to the

action. Timing can also affect the perception of mass of an object. A heavier

object takes a greater force and a longer time to accelerate and decelerate.

For example, if a character picks up a heavy object, e.g., a bowlng ball, they

should do it much slower than picking up a light object such as a basketball.

Similarly, timing affects the perception of object size. A larger object moves

more slowly than a smaller object and has greater inertia. These effects are

done not by changing the poses, but by varying the spaces or time (number of

frames) between poses.

Anticipation

Anticipation can be the anatomical preparation for the action, e.g., retracting

a foot before kicking a ball. It can also be a device to attract the viewer's

attention to the proper screen area and to prepare them for the action, like

staring off-screen at something and then reacting to it before the action moves

on-screen.

Follow Through and Overlapping Action

Follow through is the termination part of an action. An example is in throwing

a ball - the hand continues to move after the ball is released. In the movement

of a complex object different parts of the object move at different times and

different rates. For example, in walking, the hip leads, followed by the leg

and then the foot. As the lead part stops, the lagging parts continue in motion.

Heavier parts lag farther and stop slower. Overlapping means to start a second

action before the first action has completely finished. This keeps the interest

of the viewer, since there is no dead time between actions.

Rotoscoping

The idea of copying human motion for animated characters is not new. To get

convincing motion for the human characters in Snow White, Disney studios traced

animation over film footage of live actors playing out the scenes. This method,

called rotoscoping, has been successfully used for human characters ever since.

In the late 1970's, when it began to be feasible to animate characters by computer,

animators adapted traditional techniques, including rotoscoping.

|

|

|

Muybridge motion study

|

Rotoscope in Flash

|

References

The Library of Congress Video Collection, Volume 3: Origins of American Animation, 1900-1921.

http://www.siggraph.org/education/materials/HyperGraph/toc.htm

www.iath.virginia.edu/utc/onstage/lantern/

coas.missouri.edu/anthromuseum/ethno/asia.html

http://photo.ucr.edu/photographers/muybridge/